Chicago Sun Times | July 27, 2008 Sunday | Final Edition

Why is bias vs. Muslims acceptable in America?

BYLINE: Deborah Douglas, The Chicago Sun-Times | SECTION: NEWS; Deborah Douglas; Pg. A25 | LENGTH: 662 words

Raafat Arman, a Palestinian, college-educated, Republican real estate developer who lives in East Garfield Park, is as American as they come. For one thing, the guy loves money:

“I’m a hustler, babe,” says Arman, 38. “If you give me a good price for this shirt, I’ll go home in a T-shirt.”

Arman also is inspired by quintessential Americana, like repeated showings of “It’s a Wonderful Life,” and reading Think and Grow Rich. But as a secular Muslim, Arman knows people don’t look at him as a real American. He knows what it’s like to be classified as “other” in a lily-white community or a struggling black one where neighbors resent immigrant shopkeepers.

Outward antipathy toward Islam and Muslim Americans is one of America’s most accepted expressions of prejudice today, right up there with hating fat people. Consider that every time the rumor that Sen. Barack Obama is a Muslim in Christian disguise pops up — folks breathe a collective sigh of relief when they find out all over again he’s not Muslim.

Why is being the un-Muslim cause for relief?

We are the same country whose forebears came here to seek religious freedom, right? Many African slaves were Muslim, snatched from countries that practiced one of the world’s oldest religions to help build one of the world’s greatest countries. But non-Muslim blacks, like many white Americans whose families have been here for generations, quietly and not-so-quietly reject the right of the other brown people in our midst to feel and be fully American.

The real problem I had with the New Yorker magazine cover that parodied the Obamas is that it showcased an all-too-accepted view that being Muslim is somehow subversive in and of itself. (I didn’t like Michelle’s afro, either. It needed to be picked out more.)

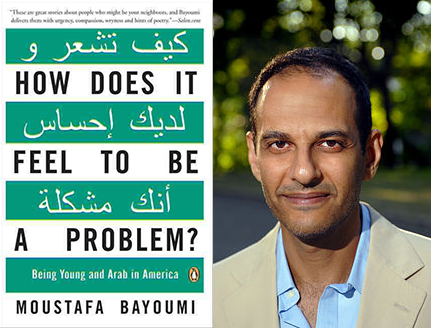

Ironically, Arabs and Muslims living in America often feel what it’s like to be black every day: Racially profiled, held suspect and rejected for jobs because your name doesn’t sound white-bread enough. This paradox is what led Moustafa Bayoumi to write How Does It Feel to Be a Problem: Being Young and Arab in America. Based on W.E.B. DuBois’ question posed in the classic The Souls of Black Folk, Bayoumi’s book will be released in August.

“A century later, Arabs and Muslims are the new ‘problem’ of American society,” Bayoumi writes. Previous “problems” include Native Americans, deemed savages; Irish and Italian Catholics in the 19th century; German Americans in World War I, and Jewish Americans between world wars.

“In a lot of ways, you can compare the situation of Muslims in the West to the way Jewish people have been talked about in the past, which is a fifth column, that their allegiances lies somewhere else,” Bayoumi says. “It’s all mythology. And it’s a powerful one that can mobilize people to oppose a minority group.”

The mythology around Islam is called up daily. The same country that prides itself on being so full of Christian love has no problem closing its mind to the diversity that lies within Islam.

That’s why Bayoumi’s book fascinates. He chronicles the life stories of seven Arab Muslim Brooklynites — their search for love, work, purpose and a place in the America they call home. Just as there are Christians who have distorted the gospel, so too are there Muslims who have committed great violence in the name of Islam. For example, John Hagee, an evangelical pastor, has denounced Catholicism as a “Godless theology.” Pastor Rod Parsley asserts America was partly founded to see Islam, a “false religion,” destroyed.

They don’t sound like my kind of Christian.

Universal dislike of “other” wouldn’t be so hurtful if it didn’t translate to mistreatment. Bayoumi recounts how racial profiling landed one family in immigration detention — a k a prison.

I’m just suspicious of passive acceptance of any ethnic stereotype. Today it’s

OK to express outward hatred toward Muslims. Tomorrow, it might be me. Or you